Where You Go, I Go: The Lives and Deaths of Ida and Isidor Straus

Credit: Getty Images

When people think of the Titanic story, the story of the Strauses nobly refusing to leave the Titanic or each other usually sticks out. Their act of selfless bravery and love have appeared in many retellings of the Titanic in movie, miniseries, literary, and audio forms. As iconic as their story is, it is worth looking at their story to tell the story of what exactly happened to them.

Early Life

Isidor Straus was born on February 6, 1845 in Otterberg, Bavaria, Germany to Lazarus and Sara Gerothwohl Straus. He was the oldest of 6 children including two brothers named Nathan and Oscar, all born in Bavaria. Isidor was 9 years old when his father who proceeded the family to America called for them and they voyaged across the Atlantic to join Lazarus in 1854. They sailed on a paddlewheel steamer called the SS St. Louis which brought them to New York and they joined Lazarus in America. This was Isidor’s first of multiple times crossing the Atlantic. Lazarus worked as a peddler in Georgia before starting a mercantile store in the small town of Talbotton, GA. Life in Talbotton was pleasant for the Straus family. Lazarus ran the store with his sons where they gained great experience and were educated in local schools. As the only Jews in the community, Lazarus arranged with the local Epsicopalian minister to teach the children from the first 5 books of the Bible. The family lived in a small 2 room house. Their quiet life quickly changed with the outbreak of the Civil War. Many men from Talbotton marched off to fight and Lazarus, seizing the business opportunity, sold supplies to the Confederates. One wonders if Lazarus was reminded of his grandfather who sold supplies to Napoleon’s army. Isidor wished to join the army and made plans to do so, heavily considering going to West Point before the war. After the war began, he attempted to help organize a company to fight for the Confederates, but was not successful because they didn’t have enough weapons. Instead, he went to work for Lloyd G. Bowers and assisted him in purchasing steamers for running blockades, smuggling much needed supplies past Union blockades in southern ports. He did some traveling during the war, but stayed away from the fighting. During Isidor’s travels, he met Mr. Nathan Bluen/Blun, a fellow immigrant from Germany who was a clothing merchant in New York. He was introduced to Nathan by his oldest daughter Amanda. After the end of the war, he returned to Georgia and moved with his family up to New York. This proved to be a wise move as the Reconstruction period following the Civil War caused many people to struggle economically and financially.

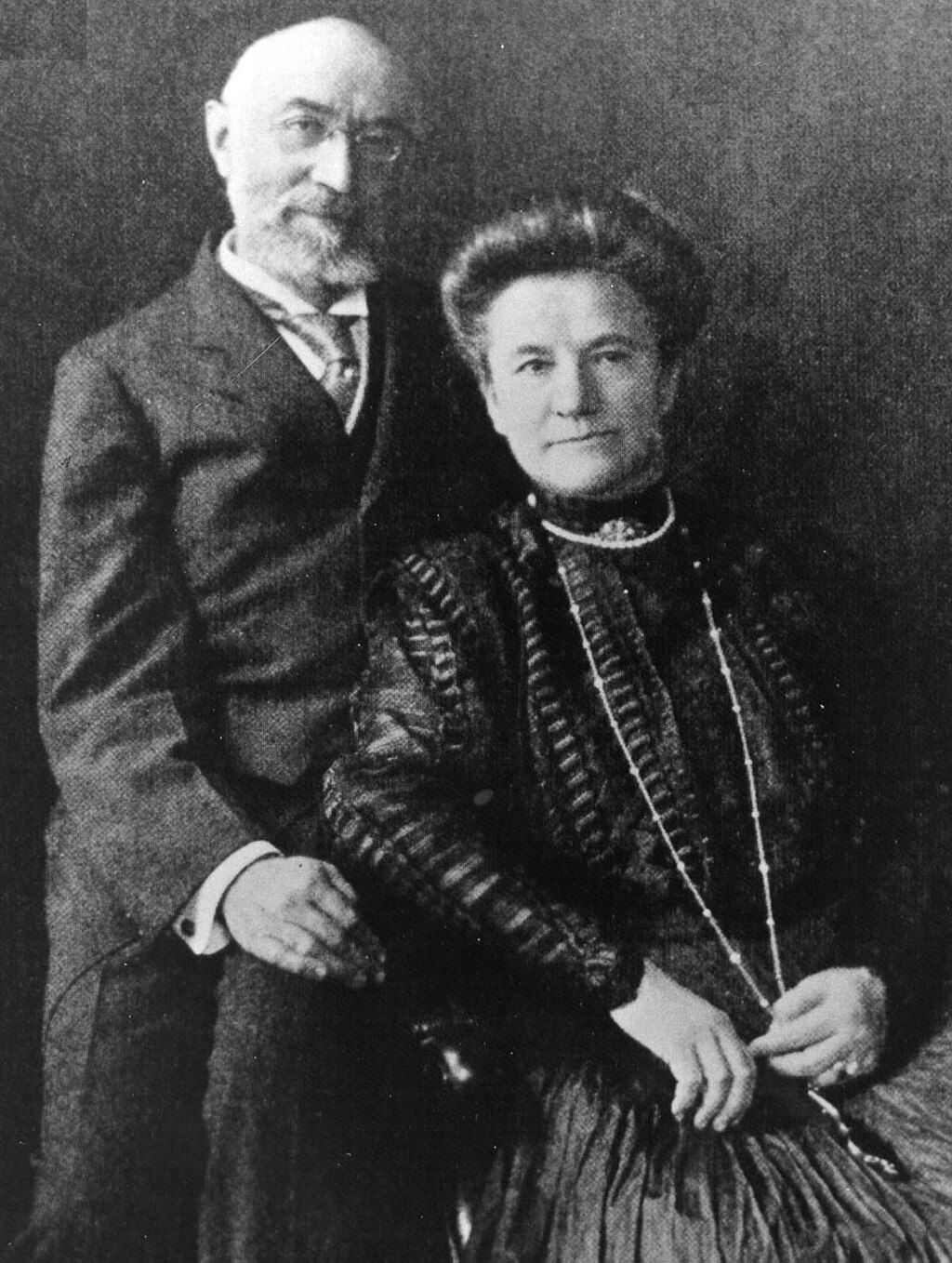

Ida and Isidor Straus when they got married.

Credit: Straus Historical Society

New Beginnings

The Strauses took their money from selling their home and business in Georgia and started a business selling china and crockery called L. Straus & Sons. One of the businesses they worked with was R.H. Macy’s Department Store in New York and even ran their glassware department. They entered a business partnership with Macy’s in 1888. Isidor later became aware of Mr. Nathan Blun’s other daughter, Rosalie Ida Blun. They shared a birthday, except she was 4 years younger. On April 24, 1871, Isidor became engaged to Ida. They were married on July 12th of that same year. Together, they had 7 children. Their names were Jessie Isidor (1872-1936), Clarence Elias (1874-1876), Percy Solomon (1876-1944), Sara (1878-1960), Minnie (1880-1940), Herbert Nathan (1881-1933), and Vivian (1887-1967). As Isidor Straus’s autobiography said, letters between Isidor and Ida indicated that Isidor focused on running the business and providing for his family while Ida ran the household. In 1876, the Straus family had a major loss when the matriarch of the family, Sara, passed away. Meanwhile, Business started to take off as Isidor and his brother Nathan worked on expanding the family firm.

The Straus Family and Politics

Meanwhile, Oscar started his law practice after graduating from Columbia, but went into business before being appointed Minister to Turkey by President Cleveland. This was the start of a fascinating and notable political career. The Straus family knew President Cleveland, having all been from New York. Isidor focused on tariffs and became very familiar with finances as well as politics and taxes. Isidor’s knowledge made him an invaluable unofficial advisor to Clevleland. In February 1893, Isidor was offered the position of Postmaster General which he declined. Had he accepted the offer, Isidor Straus would have become the first Jewish Presidential cabinet secretary in history. That honor later went to Oscar Straus who served as Secretary of Commerce and Labor under Theodore Roosevelt. Isidor was called upon by Cleveland again to advise on a financial crisis in July of 1893. Cleveland had to decide whether or not to call an emergency session of Congress to help solve it. After consulting with Isidor 15 minutes before a cabinet meeting, Cleveland decided to call the session. Isidor was unsure if his counsel truly influenced Cleveland’s decision, but he was credited in the press for it. The following year in 1894, Isidor was elected in a special election to represent New York in Congress. Isidor ran on fiscal responsibility which he followed when he got into office. He opposed things that drove up taxes and taxpayer costs including the income tax which was debated at the time. Cleveland had wanted to make Isidor the Minister to Holland, but said that he could be of use to the administration in Congress. Isidor was indeed helpful, but he didn’t enjoy Congress. He left office in 1895, choosing not to run and instead return to being a businessman in the private sector. Although Isidor no longer served in an official capacity, Isidor and Cleveland continued to communicate on different matters. It seems that Isidor wasn’t the only one to make an impression on President Cleveland. Ida Straus joined the Clevelands in receiving guests for a New Year’s Day reception at the White House in 1894. In addition to being friends with the Clevelands, the Strauses were also friends with Theodore Roosevelt when he was governor of New York. His rise to Vice President and President were followed by the Strauses and even though they were Democrats, they found ways to work with Roosevelt.

In 1893, Isidor and Nathan Straus along with Simon Rothschild bought the Weschler shares of Abraham & Weschler, making it Abraham & Straus. In 1896, Isidor and Nathan became controlling owners of Macy’s Department Store. They moved the business to the building where it still is today on 34th street in 1902. The Strauses were known for their business acumen, financial understanding, and philanthropy. Nathan Straus in particular became known as a prominent philanthropist internationally, giving back especially to Jewish causes. Isidor was also involved in different organizations including hospitals and charities.

A Trip to the Holy Land and Europe

In 1911, Isidor advocated publicly for expanding the docks in New York to accompany the new Olympic and Titanic, reasoning that ships of that size would be built in the future and America needed them to assist with trade.

On January 6, 1912, Isidor and Ida Straus boarded the RMS Caronia and Isidor’s valet John Farthing. They were going to the Holy Land where as the New York Tribune reported:According to a message from Jerusalem, during their recent stay in that city Mrs. Straus visited the ghetto and later told her husband of the misery and squalor which she had witnessed. She suggested that something be done for the relief of the miserable, whereupon Mr. Straus immediately responded, “Establish a soup kitchen at once.” He then sent a letter to the Jewish authorities guaranteeing $10,000 annually for three years to support the kitchen. Since then between 500 and 600 persons have been fed through his charity daily.

New York Tribune April 27, 1912 p. 5

The Strauses spent most of the winter in Europe and then spent the end of their trip staying at Claridge’s Hotel in London. While they were there, they would visit with Mr. and Mrs. Burbidge whose husband was the managing director of Harrod’s Department Store. They also attempted to hire a French maid to bring back to America, but instead hired British maid Ellen Bird.

Ida and Isidor Straus

Public Domain

Titanic

On April 10, 1912, the Strauses boarded the RMS Titanic in Southampton for returning to New York with John Farthing and Ellen Bird. Stewardess Violet Jessop remembered: “Next appeared a delightful old couple -old in years and young in character-whom we were always happy to see join us; Mr. and Mrs. Straus had grown old so gracefully and so together. They were, as usual, charmed to see us and with all the arrangements made for their comfort. They gave each of us an individual word of greeting as they made their way to the deck above to wave farewell to friends” (Jessop, 1997, p. 119). When he arrived on deck, Isidor met fellow 1st class passenger Archibald Gracie IV. They stood near him as the Titanic disembarked from Southampton. He later recounted:“I was with them on the deck the day we left Southampton and witnessed that ominous accident to the American liner, New York, lying at her pier, when the displacement of water by the movement of our gigantic ship caused a suction which pulled the smaller ship from her moorings and nearly caused a collision. At the time of this, Mr. Straus was telling me that it seemed only a few years back that he had taken passage on this same ship, the New York, on her maiden trip and when she was spoken of as the “last word in shipbuilding.” He then called the attention of his wife and myself to the progress that had since been made, by comparison of the two ships then lying side by side. During our daily talks thereafter, he related much of special interest concerning incidents in his remarkable career, beginning with his early manhood in Georgia when, with the Confederate Government Commissioners, as an agent for the purchase of supplies, he ran the blockade of Europe. His friendship with President Cleveland, and how the latter had honored him, were among the topics of daily conversation that interested me most” (Gracie, A. 1913). Even though Gracie said Ida was there, a letter written by Ida later that day indicated that only Isidor was there.

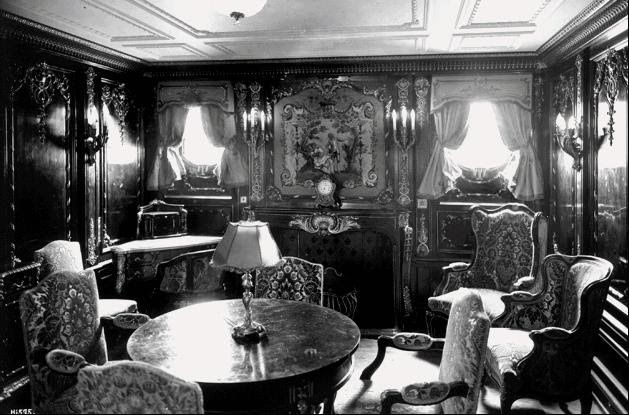

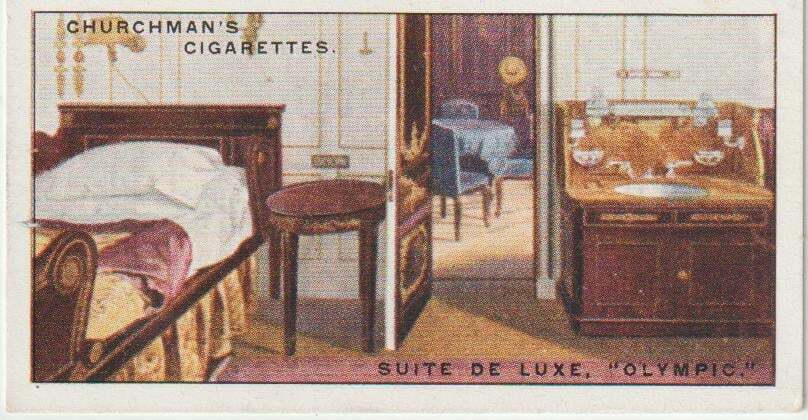

C-55, Ida and Isidor's sitting room which was in the Regency Style.

Credit: NMNI

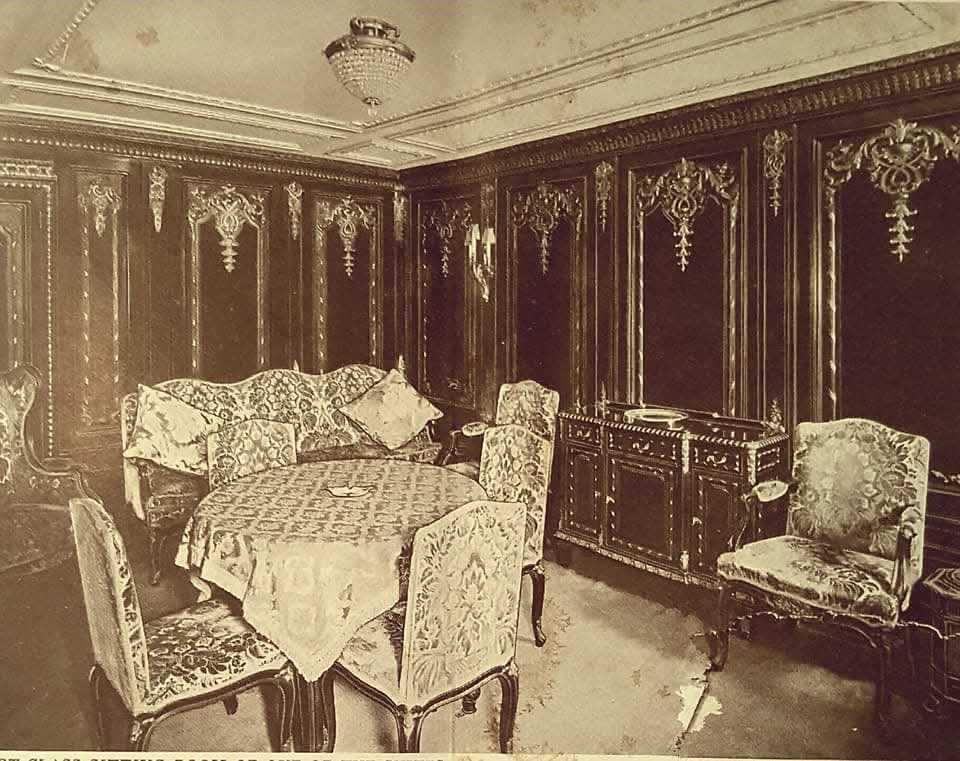

A different view of C-55.

Joshua Noble Collection

C-57 which was Ida and Isidor's bedroom in the Empire Style.

Joshua Noble Collection

A cigarette card showing colorized image of Ida and Isidor's bedroom.

Joshua Noble Collection

Note: No photos of this suite exists from 1912 of the Titanic. The images above are from her nearly identical twin sister ship Olympic.

The Strauses booked one of the most luxurious suites on the Titanic, known as a parlor suite. Located on C-Deck, their suite consisted of a sitting room and a bedroom near the forward Grand Staircase. Ellen Bird and John Farthing had simpler 1st class cabins on C-Deck so they could easily get to the Strauses during the voyage. Upon boarding, they were pleased to find that an “exquisite basket of roses and carnations” were brought to their suite by a friend, Mrs. Burbidge. She went on to say in her letter to Mrs. Burbidge: “But what a ship! So huge and magnificently appointed. Our rooms are furnished in the best of taste and most luxuriously, and they are really rooms, not cabins” (On Board The RMS Titanic, 2017). She went on to indicate how Mr. Straus witnessed the near collision, which implied she was not there despite Gracie saying otherwise. The accommodations and offerings of the Titanic are well-known. Also offered on the Titanic was Kosher food served on Kosher tableware with food prepared in a Kosher kitchen and chef. It is unknown if the Strauses took advantage of this. Kosher food was not commonly offered on ocean liners of the time and they likely were accustomed to not keeping Kosher. The Titanic’s passenger list would have included people the Strauses knew prior to this voyage including John Jacob Astor IV and his wife Madeleine, Benjamin Guggenheim, and Edgar and Leila Meyer. Mrs. Emma Schabert said that her cabin was near Ida and Isidor and that they spoke frequently during the voyage.

On April 14, 1912, they encountered Archibald Gracie again who said: “On this Sunday, our last day aboard ship, he finished the reading of a book I had loaned him, in which he expressed intense interest. This book was “The Truth About Chickamauga,” of which I am the author, and it was to gain a much-needed rest after seven years of work thereon, and in order to get it off my mind, that I had taken this trip across the ocean and back. As a counter-irritant, my experience was a dose which was highly efficacious. I recall how Mr. and Mrs. Straus were particularly happy about noon time on this same day in anticipation of communicating by wireless telegraphy with their son and his wife on their way to Europe on board the passing ship Amerika. Some time before six o’clock, full of contentment, they told me of the message of greeting received in reply. This last good-bye to their loved ones must have been a consoling thought when the end came a few hours thereafter” (Gracie, A. 1913). In that brief interaction with their son Jesse Isidor over the wireless telegraph messages, Isidor said, “fine voyage fine ship feeling fine what news.” That evening, they had their meal in the A La Carte Restaurant where a dinner party hosted by the Wideners with Captain Smith as the guest of honor took place. Lady Duff-Gordon, who was also there, recalled that they dined with John and Madeleine Astor.

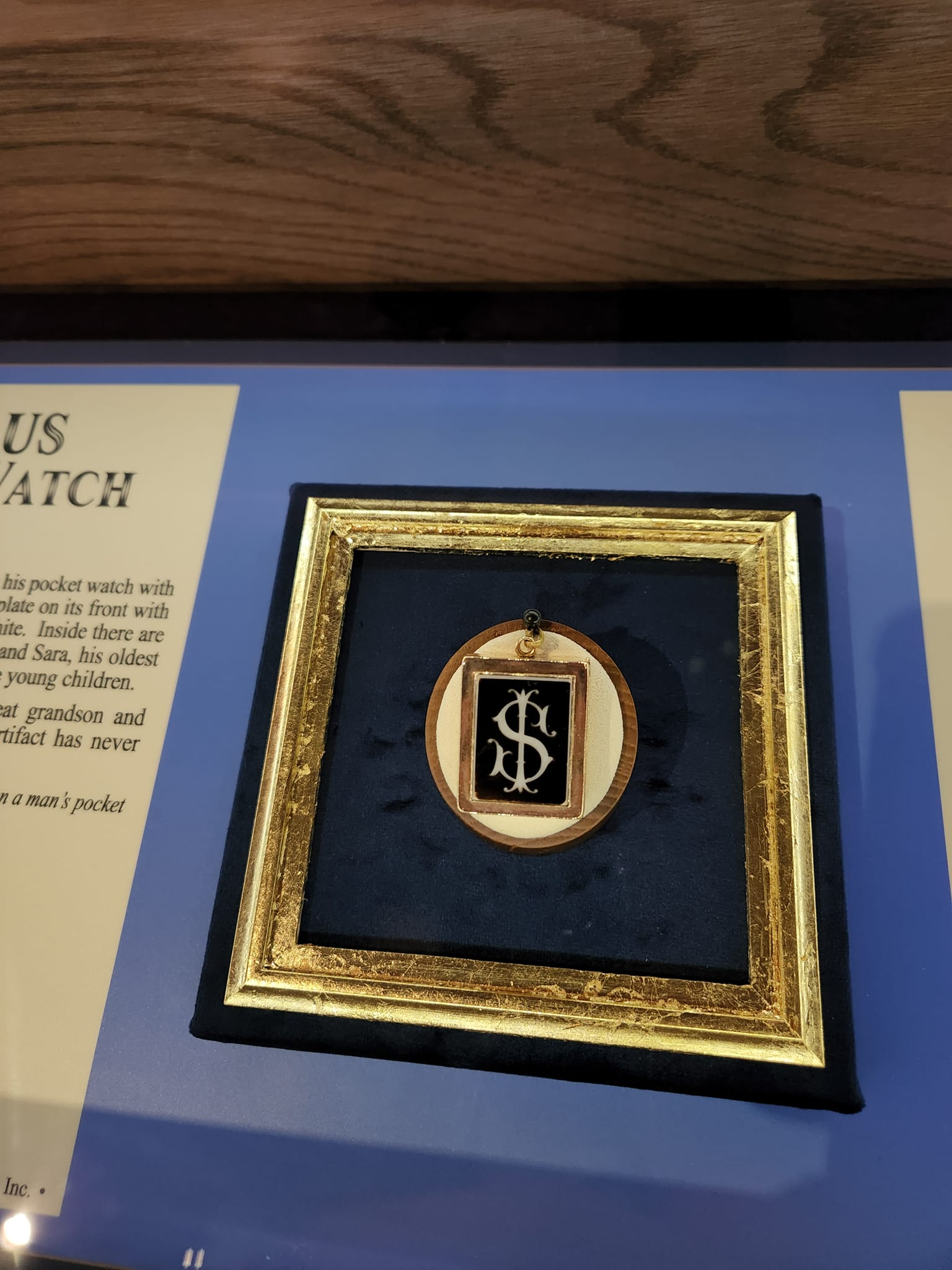

At 11:40, the Titanic struck an iceberg which caused her to start to sink. Carpathia passenger John Alexander Badenoch who knew the Strauses asked survivors about what they saw of the Strauses and said that when the crash came, they immediately appeared in the companionway, but were reassured that there was practically no danger. They returned to their cabin (Behe, 2015). Afterwards, Bedroom Steward Alfred Thessinger said:“Mr. and Mrs. Isador Strauss occupied Stateroom No. 50. As I knocked at the door Mr. Straus asked: ‘What is it steward?’ I answered: ‘Water is coming in fast. The ship is sinking.’ ‘I will get up, but I don’t think it is serious as all that,’ he answered.”In their cabin, they put on warm clothing donning fur coats with the assistance of Ms. Bird and Mr. Farthing. Isidor put on a grey suit and brown boots. In addition to typical things in his pocket like his watch and pocketbook were a flask and a silver salts bottle. Last but not least, Isidor’s effects included a fob locket with I.S. on the cover. Inside were photos of his children.

Isidor Straus's fob locket.

Credit: Straus Historical Society/Titanic Museum Attraction Pigeon Forge

From what Mr. Badenoch could gather (likely from Ellen Bird), they chatted for some time about the seriousness of the situation while the crew were getting the boats ready. Finally, the Strauses were convinced to put on life jackets. 2nd class passenger Imanita Shelley and her mother Luttie Parrish were making their way up the staircase when they said that they encountered the Strauses about half way up. Imanita said in her deposition for the US Inquiry that the Strauses helped Luttie, who was in poor health, up the stairs to the top deck. When they reached the upper decks, they made Luttie sit down and Mrs. Straus wrapped her cloak around Luttie. They went out on deck where Mr. Gracie noticed them along with the Astors on the port side of A-Deck. Gracie later told the US Inquiry: “I saw that these four ladies, with whose safety I considered myself entrusted, went beyond that line to get amidships on this deck, which was A deck. Then I saw Mr. Straus and Mrs Straus, of whom I had seen a great deal during the voyage. I had heard them discussing that if they were going to die they would die together. We tried to persuade Mrs. Straus to go alone, without her husband, and she said no. Then we wanted to make an exception of the husband, too, because he was an elderly man, and he said no, he would share his fate with the rest of the men, and that he would not go beyond. So I left them there.” He also wrote in his book “The Truth About The Titanic” about that encounter: “The self-abnegation of Mr. and Mrs. Isidor Straus here shone forth heroically when she promptly and emphatically exclaimed: “No! I will not be separated from my husband; as we have lived, so will we die together;” and when he, too, declined the assistance proffered on my earnest solicitation that, because of his age and helplessness, exception should be made and he be allowed to accompany his wife in the boat. “No!” he said, “I do not wish any distinction in my favor which is not granted to others.” As near as I can recall them these were the words which they addressed to me. They expressed themselves as fully prepared to die, and calmly sat down in steamer chairs on the glass-enclosed Deck A, prepared to meet their fate. Further entreaties to make them change their decision were of no avail. Later they moved to the Boat Deck above, accompanying Mrs. Straus’s maid, who entered a lifeboat” (Gracie, A. 1913). After realizing that they could not be persuaded, Gracie moved on. The Strauses were next spotted on the Boat Deck, having moved up as the first boats were being lowered. 1st class passenger Isaac Frauenthal looked up and saw the Strauses standing at the rail of the starboard side. He described them as being “a little removed from the other passengers and were calmly conversing” (On A Sea Of Glass, 2013 p. 191).

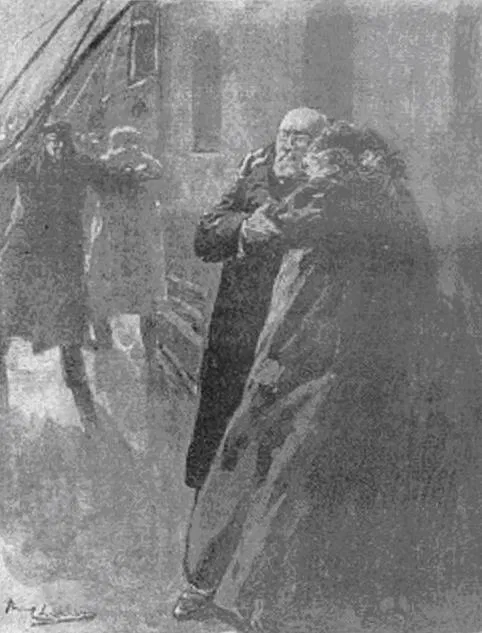

An officer attempts to convince the Strauses to get into a lifeboat. This was a 1912 illustration.

After that, they were encountered by 2nd Officer Charles Lightoller. He said: “As I returned along the deck (after distributing revolvers amongst the senior officers), I passed Mr. and Mrs. Strauss (sic) leaning up against the deck house, chatting quite cheerily. I stopped and asked Mrs Strauss, ‘Can I take you along to the boats?’ She replied, ‘I think I’ll stay here for the present.’ Mr. Strauss, calling her by her Christian name said, smilingly, ‘Why don’t you go along with him, dear?’ She just smiled, and said, ‘No, not yet. I left them, and they went down together.”

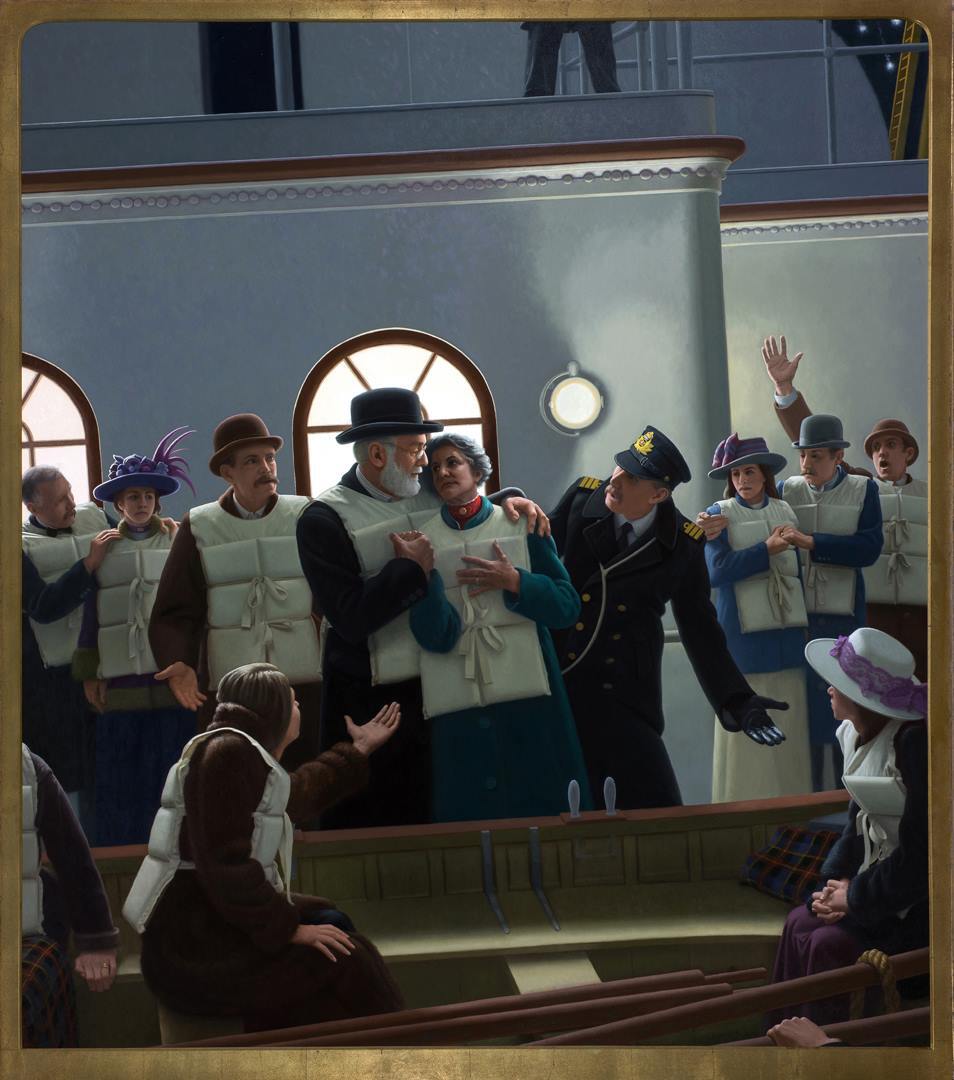

The Strauses refuse to leave each other at Boat No. 8.

Painting by Stephen Gjertson

As Boat No. 8 was being loaded, Isidor and Ida approached it. It was the first lifeboat being launched on the port side. The steam was towards the end of being released from the funnels, creating difficulty hearing. However, a few near them could hear what was being said. Their maid Ellen Bird was standing next to them and she recounted: “Mr. Straus stepped aside when the first boat was being filled, explaining that he could not go until all the women and children had places. ‘Where you are, papa, I shall be,’ spoke up Mrs. Straus, rejecting all entreaties to enter the boat. Mr. Straus vainly attempted to persuade his wife to enter the second boat, assuring her that eventually he would find a place after all the women and children had been taken off. One after another the boats were lowered. Finally that in which Mrs. John Jacob Astor was rescued was made ready. ‘Here is a place for you, Mrs. Straus,’ cried Mrs. Astor. Mrs. Straus only shrank closer to her husband. Several passengers, at least two of them being women, attempted to force Mrs. Straus into the boat, but she cried out against separation from her husband, and ordered her maid, Miss Bird, to take the place beside Mrs. Straus. “‘You go,’ said Mrs. Straus to me; ‘I must stay with my husband.’” New York Tribune April 21, 1912 p. 4

Bedroom Steward Alfred Crawford was also nearby, as he was being assigned to help man the lifeboat. He later testified at the US Inquiry:

Did you know Mr. and Mrs. Straus [Isidor and Ida Straus]?

- I stood at the boat where they refused to get in. Did Mrs. Straus get into the boat?

- She attempted to get into the boat first and she got back again. Her maid [Ellen Bird] got into the boat.What do you mean by "she attempted" to get in?

- She went to get over from the deck to the boat, but then went back to her husband.Did she step on the boat?

- She stepped on to the boat, on to the gunwales sir; then she went back.What followed?

- She said, "We have been living together for many years, and where you go I go."To whom did she speak?

- To her husband.Was he beside her?

- Yes; he was standing away back when she went from the boat.You say there was a maid there also?

- A maid got in the boat and was saved; yes, sir.Did the maid precede Mrs. Straus into the boat?

- Mrs. Straus told the maid to get into the boat and she would follow her; then she altered her mind and went back to her husband.Which one of the boats was that?

- No. 8, on the port side.

US Inquiry Day 1

In addition to Bird and Crawford, 1st class passenger Lily May Futrelle said that she saw Mrs. Straus refused to leave her husband and when an officer tried to induce her to get into a boat, she told him “No, we are too old, we will die together.” Mrs. Swift and Dr. Alice Leader who also witnessed Mrs. Straus’s actions changed their minds about boarding a lifeboat and decided to get in (On A Sea Of Glass, 2013). From the boat, Able Bodied Seaman Thomas Jones who was in charge of Boat No. 8 saw the Strauses refuse to separate, but could not hear what they were saying due to the steam. He later testified:

“I jumped in the boat. The captain asked me was the plug in the boat, and I answered, "Yes, sir." "All right," he said, "Any more ladies?" There was one lady came there and left her husband, She wanted her husband to go with her, but he backed away, and the captain shouted again - in fact, twice again - "Any more ladies?" There were no more there, and he lowered away.” US Inquiry Day 7

There are additional accounts which may have described this moment at Boat No. 8 or a different discussion as the accounts indicate similar discussions happening over and over again throughout the night, giving the Strauses multiple chances. It should be pointed out that Mr. Woolner and Mr. Bjornstrom-Steffanson were together for much of the sinking and were likely remembering the same conversation, likely when they were congregated on A-Deck early in the sinking.

1st class passenger Hugh Woolner: “After the crash,” Mr. Woolner said, “I ran to the top deck. I saw Isidor Straus near me. He was urged to get into a boat almost filled with women. He refused saying, ‘The women first.’ His wife then threw her arms around his neck.”New York Tribune April 19, 1912 p. 3

She would not get in. I tried to get her to do so and she refused altogether to leave Mr. Straus. The second time we went up to Mr. Straus, and I said to him: "I am sure nobody would object to an old gentleman like you getting in. There seems to be room in this boat." He said: "I will not go before the other men."US Inquiry Day 10

1st class passenger Mauritz Bjornstrom-Steffanson: Bjornstrom Steffanson, an attache of the Swedish Legation, said: “In the excitement I heard some one say, ‘Mrs. Straus, you must go.’ Turning around, I saw the Strauses standing together. The men were talking to Mrs. Straus. ‘No, no; I will not go!’ she cried to her husband; I cannot leave you!” Then some one said: ‘You both can go. There’s room for both.’ ‘As long as there is a woman on this vessel,’ said Mr. Straus. ‘I will not leave. They are the first who must be looked after. When they are safe then come the men. But not until all the women are in the boats will I put my foot in a lifeboat.’ ‘You are an old man, Mr. Straus,’ somebody said. ‘I am not too old to sacrifice myself for a woman,’ was the reply. “The struggle which ensued when Mr. Straus tried to force his wife into the boat is a picture which I shall never forget. It was more than pitiful. Mrs. Straus won it, and went down with her husband when the Titanic sank.”New York Tribune April 21, 1912 p. 4

1st class passenger Robert Daniel:

““Mr. Straus was urged to take a place in the boats a half a dozen times,” he said. “I heard one appeal, when a man said to him: ‘No one would object, Mr. Straus; you are an elderly man, and you have your wife with you; you’d better go.’ Mr. Straus only shook his head quietly. His wife entreated him, but he just answered her that she must go and all the women must go. He would not consider himself.”

New York Tribune April 20, 1912 p. 2

Other Sightings

When 1st class passengers Albert and Vera Dick got into Boat No. 3, they remembered seeing the Strauses near the boat and said: “As our boat, the last boat of all to go, moved away from the ship we could plainly see Mr. and Mrs. Straus standing near the rail with their arms around each other. The lights of the Titanic were all burning and the band was playing. To me the most affecting episode of the whole disaster was that final glimpse of this elderly couple, hand in hand, awaiting the end together.”New York Tribune April 21, 1912 p. 4

Over by Boat No. 10, Imanita Shelley said that Ida and Isidor were with them and helped her get into the boat while Luttie Parrish was helped in by the crew (On A Sea Of Glass, 2013).

Daily Sketch April 19, 1912

While the crew of the Titanic were loading the last lifeboat to safely leave the ship, Collapsible D, Renee and Henry B. Harris were waiting nearby with Ida and Isidor. Up until that point, Mrs. Harris had refused to leave her husband’s side as well. After hearing Captain Smith comment on how Renee Harris was foolishly handicapping her husband’s chances of saving himself, Renee turned to Ida and said, “Come along, Mrs. Straus. We must make it easier for our men.” Mr. Straus responded by saying, “We’ve been together all these years, and when we must go we will go together. You are very young, my dear. Life still holds much for you. Don’t wait for my wife” (The Triumvirate, 2024). After that, Renee left in the last chance either of them had of safely leaving the ship. Collapsible D disembarked with people like Renee Harris, Hugh Woolner, and Bjornstrom-Steffanson who had tried to get the Strauses to get into the boat, while Ida and Isidor remained on deck as the ship dipped lower and lower. As the crew attempted to get Collapsible A and Collapsible B down from the roof of the officer’s quarters, a wave swept across the forward Boat Deck. Archibald Gracie IV spotted them and seems to have been the last person to see them alive before he himself was briefly dragged down with the ship. He said: “Although he pleaded with her to take her place in the boat, she steadfastly refused, and when the ship settled by the head the two were engulfed in the wave that swept her.” Sadly, Ida and Isidor did not survive the night.

Aftermath

Very soon after the survivors of the Titanic were picked up, word spread among the people on the ship that Mr. and Mrs. Straus had bravely remained together and gone down with the ship. Mr. Badenoch, who happened to be a passenger on the Carpathia and knew them, went around compiling what happened to them from survivors in an attempt to bring their family some closure knowing the truth of what happened to them in their final moments.

In New York, word of the disaster reached the Straus family and associates which caused much concern. Isidor’s private secretary Sylvester Byrnes spent hours at the New York White Star Line office to find out what happened to them. By the time he left, he was convinced that Isidor was among the victims. Meanwhile, their son Hebert Straus boarded a train bound for Halifax hoping his father would meet him there if he survived. Little was known in the ensuing days because details of what happened would not be fully known until the Carpathia docked in New York on April 18, 1912 when survivors disembarked. Survivors talked to the press about Ida and Isidor’s heroism and that combined with the fact they were not on the ship proved that they were not among the survivors. Word reached Isidor’s brother Nathan in Rome who “took the news courageously,” but “wept like a baby” when he was told of how Ida refused to desert her husband. In Cherbourg, Isidor and Ida’s son and daughter in law, Mr. and Mrs. Jesse Isidor Straus, got word of what happened. They knew through the wireless of the disaster, but did not get confirmation that his parents did not survive until they disembarked in Cherbourg. The last Jesse had heard from his parents was the telegram they sent from the Titanic as the Amerika was going the opposite direction bound for Europe at the same time. He quickly booked passage on the Lusitania to leave for New York.

In New York, many people were touched by their story. An attempt to hold a memorial at the Education Alliance was attended by 40,000 people and resulted in chaos. The meeting was called off due to the disorderly conduct of the crowd. Another memorial was held on April 29 in front of the Ohab Zedek synagogue in which many people came to hear the rabbis memorialize the Strauses, speaking of their virtues in life and their final moments.

On April 21, Oscar Straus expressed his sorrow in a letter to Eugene Meyer, the father of Titanic victim Edgar Meyer. He said, "Our hearts are sorrowing by reason of the same calamity. It would seem our beloved ones died that others might live. You have lost a son, I a sister and a second father - he was the inspiration of my life. We deeply sympathize and mourn with you" (SHS).

A Titanic victim is recovered by the crew of the Mackay-Bennett.

Credit: Nova Scotia Archives

At sea, the body of Isidor Straus was the 96th Titanic victim recovered. His effects were catalogued and stored in a bag to be returned to the family. His body was described as:

No. 96-male-Estimated age, 65-front gold tooth (partly)-grey hair and moustache.

Clothing-Fur-lined overcoat; grey trousers, coat and vest; soft striped shirt; brown boots; black silk socks.

Effects-Pocketbook; gold watch; platinum and pearl chain; gold pencil case; silver flask; silver salts bottle; £40 in notes; £4 2s 3d in silver.

First class-Name-Isador Strauss

He was deemed in good enough condition to not be buried at sea and brought back to Halifax, arriving on April 30, 1912. In Halifax, Isidor Straus and John Jacob Astor IV were the first ones to be placed in permanent coffins for transport, likely because they knew the families were waiting and had already made arrangements for transporting them. Family friend Maurice Rothschild went up to where the CS Mackay-Bennett brought the bodies back. He identified Isidor Straus and was available to assist with the identification of Benjamin Guggenheim, but he was never found. Isidor's body was turned over to Mr. Rothschild and James Reilly of Macy’s Department Store who had the body brought down to New York on the Boston express. The journey started on May 1 and he arrived on May 3. It is Jewish tradition that a body not be left alone, so I would speculate that Maurice and James took turns staying with the body during this trip. When the train arrived, members and close friends of the Straus family were there to greet them. They chose to get the body at 125th street station in order to avoid publicity. Jesse meanwhile was still trying to make it home on the Lusitania. It was supposed to get to New York on May 3, but was delayed by a day due to taking a longer course because of the ice fields in the wake of the Titanic disaster. When the Lusitania arrived on May 4, members of the Straus family were there to greet Jesse and his wife.

This left one member of the Straus siblings that they were waiting on before proceeding with the burial. Ida and Isidor’s youngest child Vivian was abroad when she got the terrible news. She boarded the SS Kronprinzessin Cecelie bound for New York which arrived on May 8. In order to save time and avoid customs, a tugboat was sent to meet Vivian and retrieve her bags. She was given an exemption by the authorities who sent customs agents to make sure she was well and her bags cleared basic requirements. Afterwards, she was reunited with her family and was brought home. With all the children of Ida and Isidor together again, they held the funeral the next day.

Isidor Straus's grave and Ida's memorial in Beth-El Cemetery

Photos courtesy of Hunter Landau

On May 8, a small service was held in the family home led by Rabbi Samuel Schuman of Temple Beth-El. After the service, the coffin which was completely banked in white carnations and roses was placed in an “automobile hearse” (as they were called then) and Isidor left his home for the final time at 2:00 PM. He was brought to Beth-El Cemetery at Cypress Hills and placed in a family vault. In addition to the family being present for the burial, members of the Guggenheim family who lost Benjamin Guggenheim and Emma Schaefer who survived the Titanic and knew them during the voyage were in attendance. Later that year, Mr. Archibald Gracie IV would pass away and be buried in the same clothes he was wearing on the Titanic. While Gracie had survived long enough to tell of their final days and hours, he joined Isidor and Ida in death a short time later.

After his burial, the family read the last will and testament of Isidor. While Isidor’s will did not specify which charities to donate part of their fortune to, the will stated that his sons were aware of what he wanted. They in turn donated $100,000 to the Education Alliance of which Mr. Straus was president and gave $85,000 to various philanthropies. He made his sons the trustees of the will and left money to each of his children.

The Straus Memorial Plaque at Macy's Department Store.

Photo courtesy of Hunted Landau

An outpouring of mourning came about as a result of the Straus’s loss with many touched by their courage and devotion on the Titanic. The employees of Macy’s were so touched, that they raised enough money for a memorial plaque to be placed in the store. It is still there to this day. Within 2 months of the Titanic disaster, a committee was formed to create a memorial for the Strauses. On April 15, 1915, the Straus Memorial Park was unveiled at the intersection of Broadway, West End Avenue and 106th Street, adorned by a beautiful sculpture by Augustus Lukeman. Engraved in the park is II Samuel 1:23 that says, “Lovely and pleasant were they in their lives and in their death they were not parted.”

Photos courtesy of Hunter Landau

Photos courtesy of Hunter Landau

To this day, the story of Ida and Isidor has had an enduring role as the Titanic’s story is told and retold. Of the many films that have been made about the sinking, most of them contained the Strauses in some way. They are mentioned in many books as well whether they are cameos or featured interactions.

Photo credit: 20th Century Fox

As you probably gathered from reading the accounts of the sinking, many of the films did not accurately portray their final moments with the famous 1997 film even portraying them lying in bed waiting for the end. It should also be mentioned that they are often given Yiddish accents when they likely had German or American accents. However, their story and those images stand out, however brief or whatever the inaccuracies. Though they have now been gone 113 years as of this writing, their love was so powerful, it continues to inspire people today.

In 2005, James Cameron on his final expedition to the wreck of the Titanic decided to send his ROV into the Straus suite. Although the bedroom had largely collapsed by that point, the sitting room was in beautiful condition with the clock still sitting on the mantle where Ida and Isidor last saw it before going out on deck that fateful night.

Credit: National Geographic

My thanks to David Nonini, Hunter Landau, and Evgueni Mlodik for their input on this.

Resources:

The Straus Historical Society (SHS)

Straus, I. (2011), The Autobiography of Isidor Straus, Straus Historical Society Inc.

Jessop, Violet. (1997), Titanic Survivor, (John Maxtone-Graham editor), Sheridan House

Gracie, Archibald (1913), The Truth About The Titanic, Mitchell Kinnerly

Fitch, T., Leyton, J., & Wormstedt, B. (2013), On A Sea Of Glass, Amberly Publishing

Behe, G. (2017), On Board The RMS Titanic: Memories of a Maiden Voyage, The History Press

Behe, G. (2024), The Triumvirate, The History Press

Wincour, J. (1960), The story of the Titanic as told by its survivors, Dover Publications Inc.

Abraham & Straus Collection, New York Library, https://findingaids.library.nyu.edu/cbh/arc_223_abraham_straus/

Encyclopedia-Titanica

Titanic Inquiry Project https://www.titanicinquiry.org/

New York Times April 2, 1893

New York Times October 29, 1893

New York Times January 9, 1911

New York Tribune April 19, 1912 p. 3

Chicago Examiner April 20, 1912

US Inquiry Imanita Shelley Deposition Day 18

The Times-Dispatch April 19, 1912 p. 6 (Gracie interview)

The Toledo News-Bee April 16, 1912

The Times-Dispatch April 16, 1912

Chicago Examiner April 20, 1912

New York Tribune April 20, 1912 p. 1

New York Tribune April 24, 1912 p. 1

New York Tribune April 29, 1912 p. 4

The Evening World April 30, 1912 p. 1 and 2

The Sun (New York) May 3, 1912

New York Tribune May 4, 1912 p. 2

New York Tribune May 8, 1912 p. 7

New York Tribune May 9, 1912 p. 7

Image credits:

Daily Sketch April 19, 1912

Hunter Landau Photography

Stephen Gjertson

Getty Images

20th Century Fox

National Geographic